The Dawn of Energy Independence: An Introduction to Microgrids

What is a microgrid and how does it work? A microgrid is a group of interconnected loads and distributed energy resources within clearly defined electrical boundaries that acts as a single controllable entity. It can operate either connected to the main utility grid or independently in “island mode,” using local generation sources like solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, and natural gas generators to power a localized area such as a campus, hospital, or community.

Quick Answer: How Microgrids Work

-

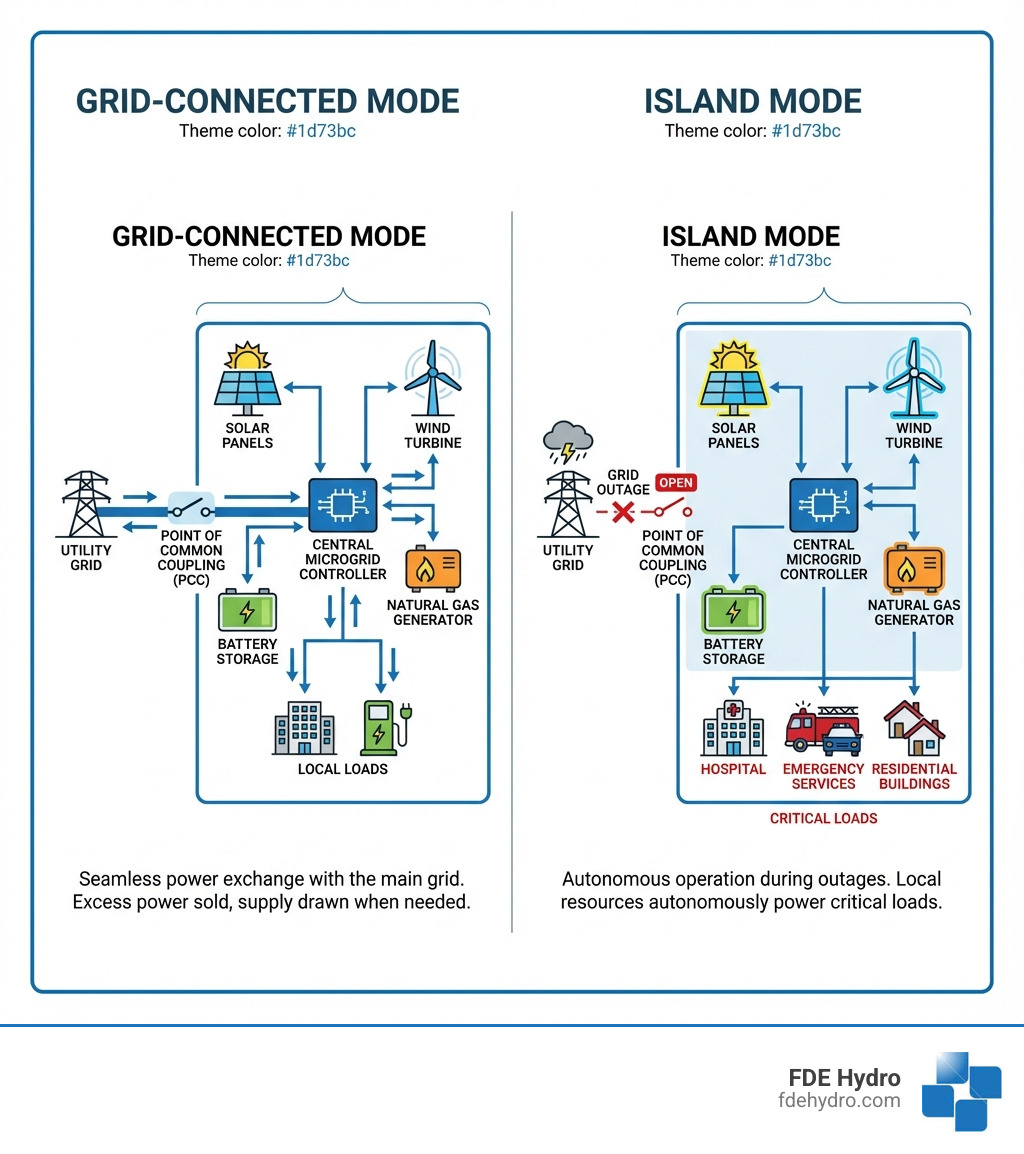

Grid-Connected Mode: The microgrid operates alongside the main utility grid, drawing power when needed, selling excess power back, or providing services like peak shaving to reduce energy costs.

-

Island Mode: When the main grid experiences an outage or disturbance, the microgrid automatically disconnects and operates independently using its local energy resources to keep critical facilities powered.

-

Key Components: A microgrid controller (the “brain”) manages distributed energy resources (solar, wind, batteries, generators), monitors grid conditions, and coordinates the seamless transition between operating modes.

When Superstorm Sandy struck in 2012, a university microgrid successfully islanded from the local distribution grid and continued to provide reliable power to its campus while also serving as a community resilience hub. This real-world example demonstrates why microgrids represent more than backup power—they’re a fundamental shift toward localized energy independence and grid resilience.

The global market for microgrids could grow to USD 55 billion by 2032, driven by falling costs of renewable energy and energy storage, increasing grid vulnerabilities, and the urgent need for resilient power systems. From airports saving $1 million annually to remote communities gaining reliable electricity for the first time, microgrids are changing how we generate, distribute, and consume power.

I’m Bill French Sr., Founder and CEO of FDE Hydro, and I’ve spent decades working on infrastructure projects that require reliable, resilient power systems. Through my participation in the Department of Energy’s Hydropower Vision Technology Task Force and extensive work in heavy civil construction, I’ve seen what is a microgrid and how does it work to support critical operations and enable sustainable energy futures. This guide will walk you through everything you need to know about these systems.

What is a Microgrid and How Does It Work?

Defining the Modern Microgrid: More Than Just Backup Power

At its heart, what is a microgrid and how does it work can be understood as a localized, self-sufficient energy system designed to provide reliable power to a specific area. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) defines a microgrid as “a group of interconnected loads and distributed energy resources within clearly defined electrical boundaries that acts as a single controllable entity with respect to the grid.” This means it has clear borders, whether it’s a university campus, a military base, or an industrial park, and it can be controlled as one cohesive unit.

This definition, highlighted in initiatives like The US DoE’s Microgrid Initiative, emphasizes its dual nature: a microgrid can operate either connected to the larger utility grid (grid-connected mode) or entirely on its own (island mode). This ability to “island” is a game-changer, allowing critical facilities to maintain power even when the main grid goes down. It’s not just about having a backup generator; it’s about intelligent, localized energy management that ensures continuity and optimizes energy use.

The Anatomy of a Microgrid: Key Components Explained

To understand what is a microgrid and how does it work, we need to dissect its core components. Think of a microgrid as a miniature version of the larger utility grid, complete with its own generation, distribution, and control systems.

The main parts include:

- Distributed Energy Resources (DERs): These are the power sources located within the microgrid’s boundaries. They can be traditional generators like diesel or natural gas, or, increasingly, renewable sources such as solar panels, wind turbines, and even hydroelectric systems—a specialty of ours at FDE Hydro. These DERs are crucial for generating electricity close to where it’s consumed, reducing transmission losses.

- Energy Storage Systems (ESS): Often comprising large battery banks, such as lithium-ion batteries, ESS are vital for balancing intermittent renewable energy sources (like solar when the sun isn’t shining) and providing instant power during grid outages. They store excess energy and release it when demand is high or generation is low.

- Microgrid Controller: This is the “brain” of the microgrid. It’s a sophisticated software and hardware system that continuously monitors grid conditions, manages the DERs and ESS, balances loads, and decides when to connect to or disconnect from the main grid. It ensures stable and efficient operation, orchestrating all the components in harmony.

- Point of Common Coupling (PCC): This is the electrical connection point where the microgrid interfaces with the larger utility grid. It’s the gateway that allows the microgrid to exchange power with the main grid or disconnect from it entirely.

- Loads: These are simply the consumers of electricity within the microgrid’s boundaries—buildings, homes, businesses, and critical infrastructure.

For a deeper dive into the fundamental concepts of electricity and energy, you might find our page on More about energy basics illuminating.

How a Microgrid Works in Its Two Primary Operational Modes

The operational flexibility of a microgrid is one of its most defining characteristics, allowing it to function effectively in two distinct modes:

-

Grid-Connected Mode: In this mode, the microgrid operates in parallel with the main utility grid, drawing power from it when local generation is insufficient or less economical, and feeding excess power back into the grid when local generation surpasses demand. This mode offers several advantages:

- Peak Shaving: By generating or discharging stored energy during periods of high demand and high utility prices, microgrids can significantly reduce electricity bills. It’s like having your own energy buffet during rush hour!

- Demand Response: Microgrids can respond to signals from the utility to reduce their consumption from the main grid, helping to stabilize the larger system during strain.

- Revenue Generation: In some regulatory environments, microgrids can sell surplus power or provide ancillary services (like voltage regulation) back to the main grid, creating an additional income stream.

-

Island Mode: This is where the microgrid truly shines in terms of resilience. When a disturbance occurs on the main grid (a blackout, storm damage, or equipment failure), the microgrid controller detects the anomaly at the PCC and automatically disconnects from the main grid. It then operates autonomously, using its internal DERs and ESS to power its local loads.

- Autonomous Operation: The microgrid controller carefully balances generation and demand within its boundaries, ensuring stable power delivery to connected facilities.

- Black Start Capability: Many microgrids are designed with the ability to “black start”—meaning they can restart their own generation sources and restore power to the local loads without any external power from the main grid. This is crucial for rapid recovery after a complete blackout.

- Seamless Islanding: The transition from grid-connected to island mode is often so quick and smooth that occupants within the microgrid may not even notice an interruption, a testament to the sophistication of modern microgrid controls.

The Powerful Payoffs: Key Benefits of Microgrids

Microgrids offer a compelling suite of advantages that address some of the most pressing energy challenges of our time, from aging infrastructure to climate change.

Best Resilience and Reliability

One of the most immediate and impactful benefits of microgrids is their ability to improve power continuity and resilience. We’ve all experienced the frustration of a power outage, but for critical facilities like hospitals, emergency services, and data centers, an outage can be catastrophic.

During Superstorm Sandy, as we mentioned earlier, the New York University microgrid successfully disconnected from the main grid and continued to provide power to much of its campus, acting as a vital lifeline and resilience hub for the community during a widespread blackout. This isn’t an isolated incident; microgrids are specifically designed to support critical infrastructure by ensuring that power keeps flowing even when the main grid fails.

By localizing power generation and distribution, microgrids can significantly reduce the duration and impact of outages. When a disturbance occurs, the microgrid simply “islands” itself, protecting its internal loads from the instability of the larger grid. This self-sufficiency means quicker recovery times and a more robust energy supply for the facilities that need it most.

Significant Economic and Efficiency Gains

Beyond resilience, microgrids offer substantial economic and efficiency benefits that can lead to impressive savings and smarter energy management.

Consider the Pittsburgh International Airport, which switched to a solar and natural gas microgrid. This strategic move led to a reported USD 1 million in savings in its first year alone, as detailed in How a microgrid saved an airport $1 Million. That’s a serious chunk of change! Similarly, a California winery built a microgrid around photovoltaic (PV) solar energy, reducing its monthly energy bills from USD 15,000 to a mere USD 1,000. These aren’t just isolated success stories; they highlight the potential for significant operational cost reductions.

A key factor in this efficiency is the reduction of transmission losses. In traditional grids, electricity can lose anywhere from 8 to 15% of its energy while traveling long distances from centralized power plants to consumers. By generating power closer to the point of consumption, microgrids minimize these losses, delivering more of the generated energy directly to where it’s needed.

Furthermore, with advanced control systems, often leveraging sophisticated algorithms and even AI in energy management, microgrids can dynamically manage energy supply and demand. They can optimize when to use local generation, when to draw from the grid, and when to store energy, all based on real-time prices and operational needs. This intelligent management contributes directly to lower operating costs and a more efficient energy ecosystem.

Accelerating Sustainable Energy Production

For us at FDE Hydro, a core mission is to advance sustainable energy solutions, and microgrids are powerful allies in this endeavor. They provide an ideal platform for integrating clean energy sources and reducing our collective carbon footprint.

Microgrids excel at incorporating diverse renewable energy technologies like solar, wind, and crucially for us, hydropower. By combining these with energy storage systems, microgrids can overcome the inherent intermittency of renewables (what happens when the sun doesn’t shine or the wind doesn’t blow?). The stored energy or a backup generator can seamlessly fill any gaps, ensuring a consistent and reliable power supply. This integration is key to achieving sustainability goals and transitioning towards a cleaner energy future.

Moreover, by enabling the widespread adoption of local renewable generation, microgrids reduce reliance on fossil fuel-based power plants, leading to fewer greenhouse gas emissions. They are a tangible step towards cleaner air and a healthier planet. Our work in developing efficient and reliable hydropower solutions, for instance, perfectly complements the microgrid model, providing a consistent, low-carbon DER. To learn more about the potential of various green technologies, explore our insights on efficient renewable resources.

From Concept to Community: Types, Challenges, and Real-World Examples

Microgrids aren’t a one-size-fits-all solution; they come in various configurations, each custom to specific needs and environments. However, their implementation isn’t without its problems.

A Spectrum of Microgrid Classifications

Understanding the different types of microgrids helps illustrate their versatility:

- Remote (Off-Grid) Microgrids: These microgrids operate entirely independently of the main utility grid, often in isolated locations where connecting to the central grid is impractical or too costly. Think remote communities in Canada or Brazil, scientific research stations, or island nations. They rely solely on their internal DERs and storage.

- Grid-Connected Microgrids: The most common type, these microgrids are physically connected to the main utility grid but have the capability to disconnect and operate autonomously when needed. They offer the best of both worlds: grid reliability for daily operations and independent resilience during outages.

- Networked Microgrids: These are more advanced systems where multiple microgrids or DERs are connected to the same utility grid circuit segment, often serving a wider geographic area. They can share resources and improve overall resilience across a larger community.

Beyond these operational classifications, microgrids can also be categorized by their scale and complexity:

- Level 1 “Single Building Microgrid”: This is the simplest form, typically serving a single building with one or more DERs, such as a solar PV system or a combined heat and power (CHP) unit, all interconnected at a single utility meter.

- Level 2 “Partial Feeder” or “Campus Microgrid”: This type serves multiple buildings or a campus (like a university or industrial park) with a single or multiple DER system, still usually interconnected at one utility meter. The New York University microgrid is a prime example of a campus microgrid.

- Level 3 “Full Feeder” or “Community Microgrid”: These are the most extensive, serving multiple buildings or customers where loads and generation sources may not be at the same utility meter. These advanced microgrids have one point of common coupling (PCC) where they can operate independently from the utility grid, providing resilience to an entire community.

Navigating the Challenges of Implementation

While the benefits are clear, deploying microgrids involves several key considerations and challenges:

- High Upfront Costs: Microgrids require significant initial investment. A 2018 study by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) found that microgrids in the Continental U.S. cost an average of $2 million-$5 million per megawatt (MW) to develop. This can be a barrier for many potential adopters.

- Regulatory Barriers: The regulatory landscape for microgrids is still evolving. Interconnection standards, tariffs for selling power back to the grid, and ownership models can vary significantly, creating complexities in planning and deployment.

- Technical Complexity: Designing, integrating, and operating a microgrid involves sophisticated engineering. Managing diverse DERs, ensuring seamless transitions between grid-connected and island modes, and maintaining power quality all require advanced technical expertise and control systems.

- Cybersecurity Concerns: As highly integrated and automated systems, microgrids are susceptible to cyber threats. Protecting the control systems and communication networks from malicious attacks is paramount to maintaining reliability and security.

Despite these challenges, the long-term benefits in resilience, cost savings, and sustainability often outweigh the initial problems. For those interested in the broader picture of developing robust energy systems, our Energy infrastructure development guide offers further insights.

Microgrids in Action: Case Studies

Real-world examples truly bring to life what is a microgrid and how does it work. We’ve already touched upon a few, but let’s dig into some others within our operational geographies:

- Pittsburgh International Airport (United States): This facility implemented a microgrid using solar and natural gas generation. As noted earlier, it saved the airport USD 1 million in its first year, demonstrating both economic viability and improved energy independence for critical infrastructure.

- New York University (New York, United States): During the widespread power outages caused by Superstorm Sandy, NYU’s microgrid successfully isolated itself from the main grid, providing continuous power to its campus. This allowed the university to serve as a vital community resource, highlighting the resilience benefits for urban centers.

- California Winery (California, United States): A great example of a smaller-scale microgrid, this winery integrated photovoltaic (PV) solar energy into its operations. The result was a dramatic reduction in monthly energy bills, from USD 15,000 to just USD 1,000, showcasing how microgrids can benefit commercial enterprises and agricultural sectors. You can find more insights into similar projects in the California microgrid case studies.

These examples, from major transportation hubs to academic institutions and agricultural businesses, underscore the diverse applications and tangible benefits that microgrids deliver.

Frequently Asked Questions About Microgrid Technology

We often get asked specific questions about microgrids, so let’s address some of the most common ones.

How do microgrids differ from the smart grid?

This is a fantastic question! While both microgrids and smart grids aim to modernize our energy infrastructure, they operate on different scales and have distinct primary functions.

- Scale: The most significant difference is scale. A microgrid is a localized energy system, typically serving a campus, a neighborhood, or an industrial facility. It has clearly defined electrical boundaries. In contrast, a smart grid is a large-scale modernization of the entire utility grid—an expansive network that covers vast geographic areas, potentially an entire state or country.

- Autonomy: A microgrid’s defining characteristic is its ability to “island”—to disconnect from the main grid and operate independently. This self-sufficiency is what provides localized resilience. A smart grid, while highly advanced with two-way communication and automation, is still fundamentally connected to and dependent on the central power generation and transmission system. It improves efficiency, reliability, and responsiveness across the entire grid, but it doesn’t typically operate autonomously in localized segments during a full grid outage.

Think of it this way: if the traditional grid is a highway system, a smart grid is an upgraded, intelligent highway with real-time traffic monitoring and automated vehicle control. A microgrid, however, is a self-contained private road system with its own power generation, capable of operating even if the main highway is shut down.

What is the role of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) in a microgrid?

Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) are the very heart of a microgrid. Without them, a microgrid wouldn’t exist! They are the small-scale, localized electricity generators and storage devices that allow a microgrid to produce power close to its consumers.

DERs can include a variety of technologies:

- Solar panels: Capturing energy from the sun.

- Wind turbines: Using wind power.

- Hydropower: Utilizing flowing water, a specialty for us at FDE Hydro, offering a consistent and powerful renewable source.

- Geothermal: Tapping into the Earth’s heat.

- Combined Heat and Power (CHP): Generating both electricity and useful heat from a single fuel source.

- Energy storage systems: Primarily batteries, which store excess energy from renewables or the grid and discharge it when needed.

These DERs enable local generation and self-sufficiency, which are fundamental to a microgrid’s operation. They allow the microgrid to reduce its reliance on the main grid, cut down on transmission losses, and provide power even during outages. For anyone looking to start on projects involving these technologies, our Guide to renewable energy projects is an excellent resource.

What is the first step to building a microgrid?

Building a microgrid is a significant undertaking, but the first step is always the most crucial: a thorough feasibility study. This isn’t just about crunching numbers; it’s about understanding needs, assessing capabilities, and charting a clear path forward.

Here’s what a comprehensive feasibility study typically involves:

- Defining Goals: What do you want your microgrid to achieve? Is it primarily for resilience during outages, significant cost savings, integrating more renewables, or a combination? Clear goals will guide all subsequent decisions.

- Identifying Critical Loads: Which facilities or processes absolutely cannot lose power? For a hospital, it’s life support and operating rooms. For a data center, it’s servers. Understanding these critical loads is paramount for designing a system that ensures their continuous operation.

- Assessing Existing Infrastructure: What power sources, electrical distribution systems, and control mechanisms are already in place? This audit helps identify what can be leveraged and what needs to be added or upgraded.

- Site Audit: A detailed physical inspection of the proposed microgrid site to evaluate space for DERs (like solar arrays or our modular hydropower solutions), assess interconnection points, and identify any environmental or logistical constraints.

- Load Data Analysis: Collecting historical electricity consumption data (ideally 12 months of 15-minute interval utility bills) to understand energy demand patterns, peak loads, and energy profiles.

This initial phase helps determine if a microgrid is technically viable and economically beneficial for your specific location and objectives.

The Future is Local: Building a Resilient Energy Tomorrow

The energy landscape is undeniably shifting. With increasing grid vulnerabilities due to aging infrastructure and extreme weather events, coupled with the urgent need for decarbonization, microgrids represent a powerful solution. The projected growth of the global microgrid market to USD 55 billion by 2032 underscores a clear trend towards energy independence and decentralization.

This shift empowers communities, campuses, and industries to take control of their energy destiny, fostering resilience against disruptions and paving the way for a more sustainable future. At FDE Hydro, we’re proud to contribute to this revolution by providing foundational hydropower components that offer reliable, clean energy generation within these localized systems. Our innovative modular precast concrete technology is designed to significantly reduce the cost and time of building and retrofitting hydroelectric dams in North America, Brazil, and Europe, making robust microgrid solutions more accessible.

As we continue to innovate and expand our capabilities, we believe that the principles of localized, resilient, and sustainable energy will define the next generation of power infrastructure. We invite you to learn more about how we can help you achieve your energy goals and explore our advanced microgrid solutions.