Understanding the Hydro Energy Power Plant

A hydro energy power plant converts the energy of moving water into electricity. Water stored behind a dam flows through a penstock, spins a turbine, which rotates a generator to produce power. This renewable energy source has powered communities for over a century and currently supplies approximately 15% of the world’s electricity—more than all other renewable sources combined.

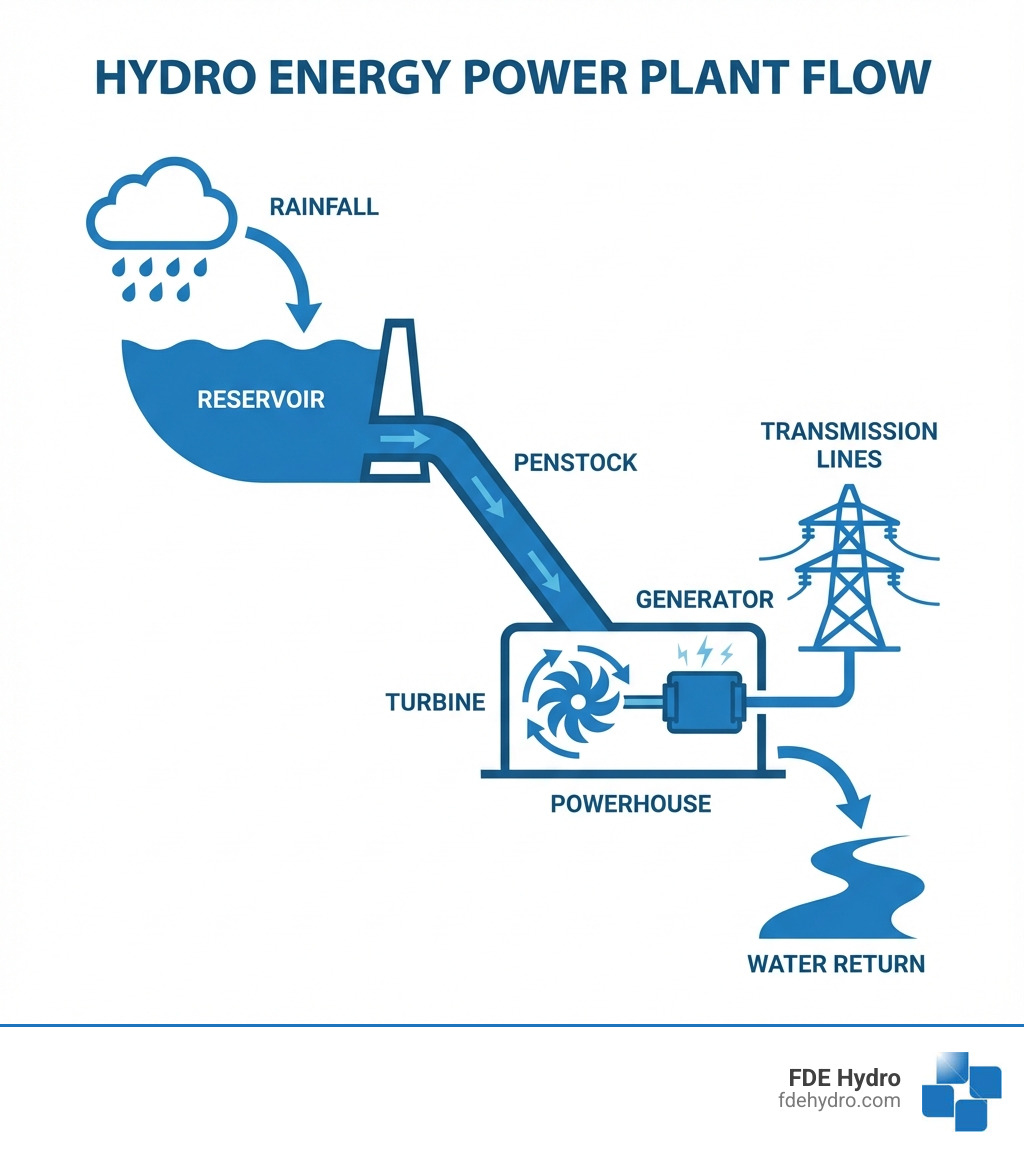

How a Hydro Energy Power Plant Works:

- Water Storage – A dam creates a reservoir, storing water at a higher elevation

- Water Release – Water flows from the reservoir through a large pipe called a penstock

- Turbine Rotation – The force of falling water spins turbine blades

- Power Generation – The turbine shaft connects to a generator, producing electricity

- Transmission – Power lines carry electricity to homes and businesses

- Water Return – Water exits through the tailrace back into the river

Humans have harnessed water power for thousands of years. Ancient Greeks used water wheels to crush grain more than 2,000 years ago. The first hydroelectric power plant opened in Wisconsin in 1882, powering just a few homes and businesses. Today, massive installations like China’s Three Gorges Dam generate 22,500 megawatts—enough to power millions of homes.

The scale of hydropower matters. In 2022, China added 24 GW of new hydropower capacity, accounting for nearly three-quarters of global additions. The United States generates about 6.2% of its total electricity from hydropower, with Washington State alone accounting for 27% of the nation’s hydropower capacity. Yet despite this long history and widespread adoption, traditional dam construction remains expensive, time-consuming, and environmentally challenging.

I’m Bill French Sr., Founder and CEO of FDE Hydro™, where we’ve developed modular construction methods that dramatically reduce the cost and timeline of hydro energy power plant projects. After five decades leading major civil construction projects—including groundbreaking work on modular bridge construction for Boston’s I-93—I’ve applied those innovations to revolutionize how the hydropower industry builds dams and powerhouses.

Easy hydro energy power plant glossary:

How Hydropower Works: From Rain to Grid

The journey of electricity generated by a hydro energy power plant begins long before the water hits a turbine. It starts with the Earth’s natural water cycle, a continuous process driven by solar energy. Water evaporates from oceans, lakes, and rivers, rises into the atmosphere, condenses to form clouds, and returns to Earth as precipitation—rain or snow. This precipitation then flows over land, collecting in rivers and streams, eventually making its way back to larger bodies of water.

This cycle is crucial for hydropower. When water is stored in a reservoir behind a dam, it possesses potential energy due to its elevation. Think of it like holding a bowling ball at the top of a hill – it has the potential to roll down. When we release this water, gravity pulls it downwards, converting that potential energy into kinetic energy – the energy of motion. It’s this kinetic energy that we harness to generate electricity. The greater the volume of water and the higher the “head” (the vertical drop), the more energy we can extract.

The Core Components of a Hydroelectric Plant

Every hydro energy power plant, regardless of its size, relies on a few fundamental components working in harmony to convert water’s kinetic energy into usable electricity.

- Dam: This is the structure that impounds water, creating a reservoir. While many dams serve multiple purposes like flood control and irrigation, our focus is on their role in storing water for power generation. It’s important to remember that not all dams generate electricity; in the U.S., less than 3% of the more than 90,000 dams actually produce power. For an in-depth look at these structures, explore our guide on Hydroelectric Dam Components Ultimate Guide.

- Reservoir: The artificial lake formed behind the dam. This body of water stores the potential energy that will be converted into electricity. Reservoirs also offer benefits like water supply, recreation, and flood control, making them multi-purpose assets.

- Penstock: A large pipeline or conduit that carries water from the reservoir to the turbine. It’s designed to withstand high pressures and guide the water efficiently.

- Turbine: A mechanical device with blades that are spun by the force of moving water. As the water rushes through the penstock and hits the turbine blades, it causes them to rotate rapidly.

- Generator: Directly connected to the turbine by a shaft, the generator is where the magic of electricity creation happens. As the turbine spins the generator’s rotor, it creates a magnetic field that induces an electric current in stationary coils (the stator), based on Faraday’s principle of electromagnetic induction.

- Power Lines: Once electricity is generated, transformers step up the voltage for efficient long-distance transmission through power lines to homes and businesses.

- Tailrace: The channel that carries the water away from the turbine and back into the river downstream.

How a Conventional Hydro Energy Power Plant Works

Let’s walk through the process of how a conventional hydro energy power plant generates electricity:

- Water Intake: Gates in the dam open, allowing water from the reservoir to enter the penstock. This controlled release ensures that the plant can respond to electricity demand.

- Turbine Rotation: The water, under immense pressure and velocity, flows down the penstock and strikes the blades of the turbine, causing it to spin at high speeds. Imagine a giant pinwheel being pushed by a powerful river!

- Generator Activation: The spinning turbine is mechanically linked to a generator. This rotation causes the generator’s internal magnets to move past copper coils, inducing an electric current. This is the heart of electricity production – converting mechanical motion into electrical energy.

- Electricity Transmission: The generated electricity is then sent to a transformer, which increases its voltage for efficient transmission across long distances through the power grid.

- Water Release: After passing through the turbine, the water exits the plant through the tailrace and re-enters the river, continuing its natural flow downstream. This means the water itself is not consumed or altered, only its energy is harnessed.

This entire process is a continuous loop, as long as there’s water flowing. For more detail on this fascinating conversion, visit our page on Hydroelectric Power Generation.

Types of Hydropower Facilities

Not all hydro energy power plants are built alike. They come in various configurations, each suited to different geographical and operational needs:

- Impoundment Facilities: These are the most common type, utilizing a large dam to store water in a reservoir. Water is released from the reservoir to spin turbines and generate electricity. Examples include the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington State, one of the largest hydro energy power plants in the United States.

- Diversion Facilities (Run-of-the-River): Instead of a large dam and reservoir, these plants divert a portion of a river’s flow through a canal or penstock to a powerhouse. They typically have little or no water storage, meaning they generate electricity based on the natural flow of the river. This approach often minimizes environmental impact on the river ecosystem.

- Pumped Storage Hydropower (PSH): This is where hydropower really shines as an “energy battery.” PSH facilities have two reservoirs at different elevations. During periods of low electricity demand (e.g., at night), we use surplus electricity from the grid to pump water from the lower reservoir to the upper one. When demand is high, the water is released back down through turbines to generate electricity, just like a conventional plant. While PSH facilities typically consume more electricity than they produce (making them a net consumer of energy), their value lies in providing crucial grid stability and storage for intermittent renewable sources like solar and wind. They allow us to store energy for months, acting as massive “water batteries.” In the U.S., these systems can store up to 553 gigawatt-hours of energy – enough to power all the country’s video gaming for about a week! Learn more about this innovative technology on our Pumped Storage Hydropower page.

The Global Scale and Historical Significance of Hydropower

Hydropower has been a cornerstone of civilization for millennia. From ancient Chinese water wheels used for grinding grain and paper making during the Han Dynasty to Richard Arkwright’s pioneering textile mills in 18th-century England, water’s power has driven progress. The modern era of hydroelectricity began in 1878 when the world’s first hydroelectric power scheme lit a single lamp at Cragside House in England. Just four years later, in 1882, the first plant supplying electricity to multiple homes and businesses opened in Wisconsin, USA.

The 20th century saw a dramatic expansion of hydropower, particularly in the United States with iconic projects like the Hoover Dam and the Grand Coulee Dam, built to provide electricity, flood control, and irrigation. These projects were instrumental in regional development and economic growth.

Globally, hydropower remains a dominant force in renewable energy. In 2023, it supplied almost 4,210 TWh, accounting for 15% of the world’s electricity. This is more than all other renewable sources combined and even surpasses nuclear power. In 2021, global installed hydropower electrical capacity reached almost 1,400 GW, the highest among all renewable energy technologies.

Major producing countries include China (30% of global hydro production in 2022), Brazil (10%), Canada (9.2%), and the United States (5.8%). China continues to lead in new capacity additions, accounting for nearly three-quarters of global hydropower capacity additions in 2022. Brazil, with its vast river systems, also relies heavily on hydropower, with projects like the Itaipu Dam (14,000 MW capacity) being globally significant. Even our neighbors to the north in Canada generate 57.5% of their electricity from hydro. For more insights into global trends, we recommend the Hydropower Special Market Report from the IEA.

From Mega-Dams to Micro-Systems

The scale of hydro energy power plants is incredibly diverse, ranging from colossal structures that power entire regions to tiny systems for individual homes.

- Large-scale Hydropower: These facilities typically have capacities greater than 30 megawatts (MW) and often involve significant infrastructure like large dams and reservoirs. The Three Gorges Dam in China is the world’s largest power-producing facility of any kind, with a staggering capacity of 22,500 MW. The Itaipu Dam, straddling Brazil and Paraguay, is another giant, with 14,000 MW. These mega-dams contribute substantially to national grids.

- Small-scale Hydropower: Generally defined as plants with capacities up to 10 MW, though this can stretch to 25-30 MW in some regions like Canada and the United States. These projects often have less environmental impact and can be integrated into existing infrastructure or natural river flows.

- Micro-hydro Systems: These are small-scale installations that typically produce up to 100 kilowatts (kW) of power. They are often used to provide electricity to small communities or isolated villages, particularly in developing regions, offering off-grid solutions where larger infrastructure is impractical.

- Pico-hydro Systems: Even smaller, pico-hydro systems generate under 5 kW. These are ideal for powering individual homes or small businesses, providing basic electricity for lighting, charging devices, and other essential needs in remote areas.

This range of scales highlights hydropower’s versatility, from powering industrial giants to bringing light to remote communities.

The Pros and Cons of a Hydro Energy Power Plant

Like any energy source, hydropower comes with its own set of advantages and disadvantages. We believe in providing a balanced perspective to understand its true role in a sustainable energy future.

| Feature | Hydropower | Solar (Utility-scale) | Wind (Onshore) | Natural Gas (Combined Cycle) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost (LCOE) | Low (once built), long operational life | Decreasing, but higher initial | Decreasing, but higher initial | Variable fuel cost, moderate capital |

| Reliability | High, dispatchable, excellent for grid stability | Intermittent (daylight only) | Intermittent (wind availability) | High, dispatchable, but relies on fuel |

| Emissions | Very low direct emissions (some reservoir methane) | Very low direct emissions | Very low direct emissions | High CO2, NOx, SO2 emissions |

| Flexibility | Very high (rapid ramp up/down, storage) | Low (requires storage for dispatchability) | Low (requires storage for dispatchability) | High (quick start/stop) |

| Lifespan | Very long (50-100+ years) | Moderate (20-30 years) | Moderate (20-25 years) | Moderate (30-40 years) |

| Land Use | High (reservoirs), but multi-purpose | High (solar farms) | Moderate (turbine footprint small, but large area) | Low (power plant footprint) |

| Water Use | Non-consumptive (re-uses water), some evaporation | Low (cooling, cleaning) | Low | High (cooling) |

| Energy Storage | Excellent (pumped storage) | Requires external battery storage | Requires external battery storage | None (fuel storage only) |

Our commitment to Sustainable Power Generation means constantly evaluating these factors.

Key Advantages of Hydropower

We find that the benefits of hydropower are compelling, positioning it as a powerful and reliable component of our energy mix:

- Renewable and Clean: Hydropower harnesses the natural water cycle, making it a truly renewable resource. During operation, a hydro energy power plant produces no direct air pollution or carbon dioxide emissions, significantly contributing to a cleaner environment compared to fossil fuels.

- Low Operating Costs: Once a hydroelectric complex is built, its fuel (water) is free. This results in very low operating and maintenance costs over its long lifespan, making it highly cost-effective in the long run.

- Long Plant Lifespan: Hydroelectric stations are incredibly durable, often remaining in service for 50 to 100 years or even longer. This longevity provides a stable and consistent source of power for generations.

- Grid Stability and Flexibility: One of hydropower’s most significant advantages is its ability to respond rapidly to changes in electricity demand. We can quickly increase or decrease power output in seconds or minutes, making it an excellent source for balancing the grid and providing backup for intermittent sources like solar and wind. This flexibility is why we consider hydropower the Guardian of the Grid.

- Baseload and Peak Load Response: Hydropower can provide steady, reliable baseload power, but it truly excels at meeting peak demand. Its quick start-up time (often just minutes from cold start to full load) means it can fill gaps when other sources falter.

- Multi-purpose Benefits: Beyond electricity, hydropower facilities often offer additional advantages like flood control, irrigation, water supply for communities (such as New York City, which relies on upstate reservoirs), and recreational opportunities.

These advantages underscore the immense value of a hydro energy power plant. Learn more about these Benefits of Hydropower Plant.

Disadvantages and Environmental Concerns

While hydropower offers many benefits, we must also acknowledge its challenges and potential environmental impacts. Understanding these helps us develop more sustainable solutions.

- High Initial Construction Costs: Building a large dam and hydro energy power plant is a massive undertaking, requiring significant upfront capital investment. These projects can be costly and time-consuming to develop.

- Ecosystem Damage: Dams fundamentally alter river ecosystems. They can disrupt natural flow regimes, change water temperature and chemistry, and impact habitats both upstream and downstream.

- Fish Migration Disruption: Dams act as barriers to migratory fish species (like salmon in the Pacific Northwest of the US or eels in Europe), preventing them from reaching spawning grounds. While solutions like fish ladders and elevators exist, they are not always 100% effective, and turbines can still cause fish mortality.

- Land Use and Displacement: The creation of large reservoirs can submerge vast areas of land, including forests, agricultural land, and even entire communities. This often leads to the displacement of human populations and loss of natural habitats. The World Commission on Dams estimated that 40-80 million people worldwide have been displaced by dams.

- Methane Emissions from Reservoirs: In some cases, particularly in tropical regions or where forests are not cleared before inundation, decaying organic matter in reservoirs can produce methane. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, and these emissions can, in certain circumstances, make the lifecycle greenhouse gas footprint of a hydro plant comparable to or even higher than fossil fuel plants. However, in temperate climates like much of the US, Canada, and Europe, these emissions are typically much lower.

- Siltation: Rivers naturally carry sediment. Over time, this sediment can accumulate in reservoirs, reducing their storage capacity and lifespan. This “siltation” can also starve downstream river sections of vital sediment, leading to erosion.

- Drought Vulnerability: Hydropower generation is directly dependent on water availability. Prolonged droughts, exacerbated by climate change, can severely reduce a plant’s output, leading to power shortages in heavily reliant regions.

- Dam Failure Risks: Although rare, dam failures due to poor construction, natural disasters, or extreme weather events can be catastrophic, causing immense loss of life and property downstream.

We recognize these are serious concerns. Our goal at FDE Hydro™ is to mitigate these impacts through innovative design and construction. For a deeper dive into these issues, please read our article on Hydropower Environmental Impact.

The Future of Hydropower: Innovation and Sustainability

The future of hydropower is not just about building new facilities, but also about making existing ones better and smarter. We see immense potential in enhancing the sustainability and efficiency of this vital renewable energy source.

One critical area is the modernization of existing plants. Many hydro energy power plants in the U.S., Canada, and Europe were built decades ago. Upgrading equipment, improving efficiency, and integrating new technologies can significantly boost output and extend their operational lives. This is a key focus for us at FDE Hydro™, and you can learn more about these efforts on our Hydropower Retrofitting page.

Another exciting prospect is powering non-powered dams. In the United States, for example, the Department of Energy estimates that thousands of existing dams, originally built for purposes like flood control or irrigation, could be retrofitted with hydropower generation capabilities, adding significant clean energy to the grid without building entirely new dam structures.

Investment trends also point to a strong future. Lending from the World Bank for hydropower development increased significantly in the past, showing continued interest in its potential. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects global hydropower capacity to grow by an additional 17%, or 230 GW, between 2021 and 2030. This growth is especially critical in developing economies, which aligns with our focus on regions like Brazil. Explore more about these trends and innovations on our Hydropower Advancements & Innovations 2025 page.

The Future of the Hydro Energy Power Plant

The next generation of hydro energy power plants will be defined by technological innovation and a stronger commitment to environmental stewardship.

- Fish-Friendly Turbines: Significant research is underway to develop turbines that minimize harm to fish passing through them. These “fish-friendly” designs, along with technologies like aerating turbines (which add oxygen to water), aim to reduce ecological impacts. The U.S. Department of Energy, for instance, has sponsored research to reduce fish deaths to lower than 2%.

- AI for Water Management: Artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing how we manage water resources. AI can optimize water release schedules based on weather forecasts, electricity demand, and environmental needs, maximizing efficiency while minimizing ecological disruption. This intelligent management is crucial for balancing power generation with ecosystem health. Find how we’re leveraging this on our AI Energy Management page.

- Innovative Construction Methods: This is where FDE Hydro™ shines. Our patented modular precast concrete technology, known as the “French Dam,” allows us to construct and retrofit hydroelectric dams and powerhouses significantly faster and more cost-effectively than traditional methods. By manufacturing dam components off-site and assembling them rapidly on-site, we reduce construction time, environmental footprint during construction, and overall project costs. This approach is particularly beneficial for projects in North America, Brazil, and Europe, where infrastructure modernization is key. Our Modular Dam Construction methods represent a leap forward in project delivery.

We are excited about these advancements and believe they will open up new opportunities for sustainable hydropower development globally. To explore our vision for this future, visit The Future of Hydropower.

Frequently Asked Questions about Hydro Energy Power Plants

How much of the world’s electricity comes from hydropower?

Hydropower supplies about 15% of the world’s electricity, making it the largest single source of renewable energy globally. In 2023, it generated almost 4,210 TWh.

Is hydropower a completely clean energy source?

While hydro energy power plants produce no direct air pollution or CO2 emissions during operation, they are not without environmental impact. The creation of reservoirs can release methane (especially in tropical regions), alter ecosystems, and affect fish populations. Our goal is to develop and implement solutions that minimize these impacts.

What is the largest hydro energy power plant in the world?

The Three Gorges Dam in China is the world’s largest power station of any kind, with an installed capacity of 22,500 megawatts (MW).

Conclusion

As we’ve explored, the hydro energy power plant stands as a foundational pillar of renewable energy, a testament to human ingenuity in using nature’s power. From ancient water wheels to modern mega-dams and innovative micro-systems, hydropower has consistently provided reliable, low-cost electricity for centuries. Its flexibility and ability to store vast amounts of energy position it as a crucial component for stabilizing our grids and integrating other intermittent renewables.

However, we must also acknowledge and address the environmental and social impacts associated with large-scale hydropower development. Our path forward lies in balancing these benefits with a strong commitment to sustainable practices. This means investing in modernization of existing infrastructure, developing fish-friendly technologies, leveraging AI for intelligent water management, and embracing innovative construction methods like our modular precast technology at FDE Hydro™.

The future of hydropower is bright, driven by continuous innovation and a renewed focus on ecological responsibility. We are committed to leading this charge, building a more sustainable and electrified world.

To learn more about our advanced solutions for modern dam construction and how we’re shaping the future of hydropower, we invite you to Explore advanced solutions for modern dam construction.