Why Understanding Hydropower’s Environmental Trade-Offs Matters

The hydropower environmental impact encompasses a complex set of ecological and social effects. While hydropower provides renewable energy without direct air pollution, it fundamentally alters river ecosystems through habitat fragmentation, disrupts aquatic life, and can release significant greenhouse gases from reservoirs—particularly in tropical regions where emissions may exceed 0.5 pounds of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt-hour.

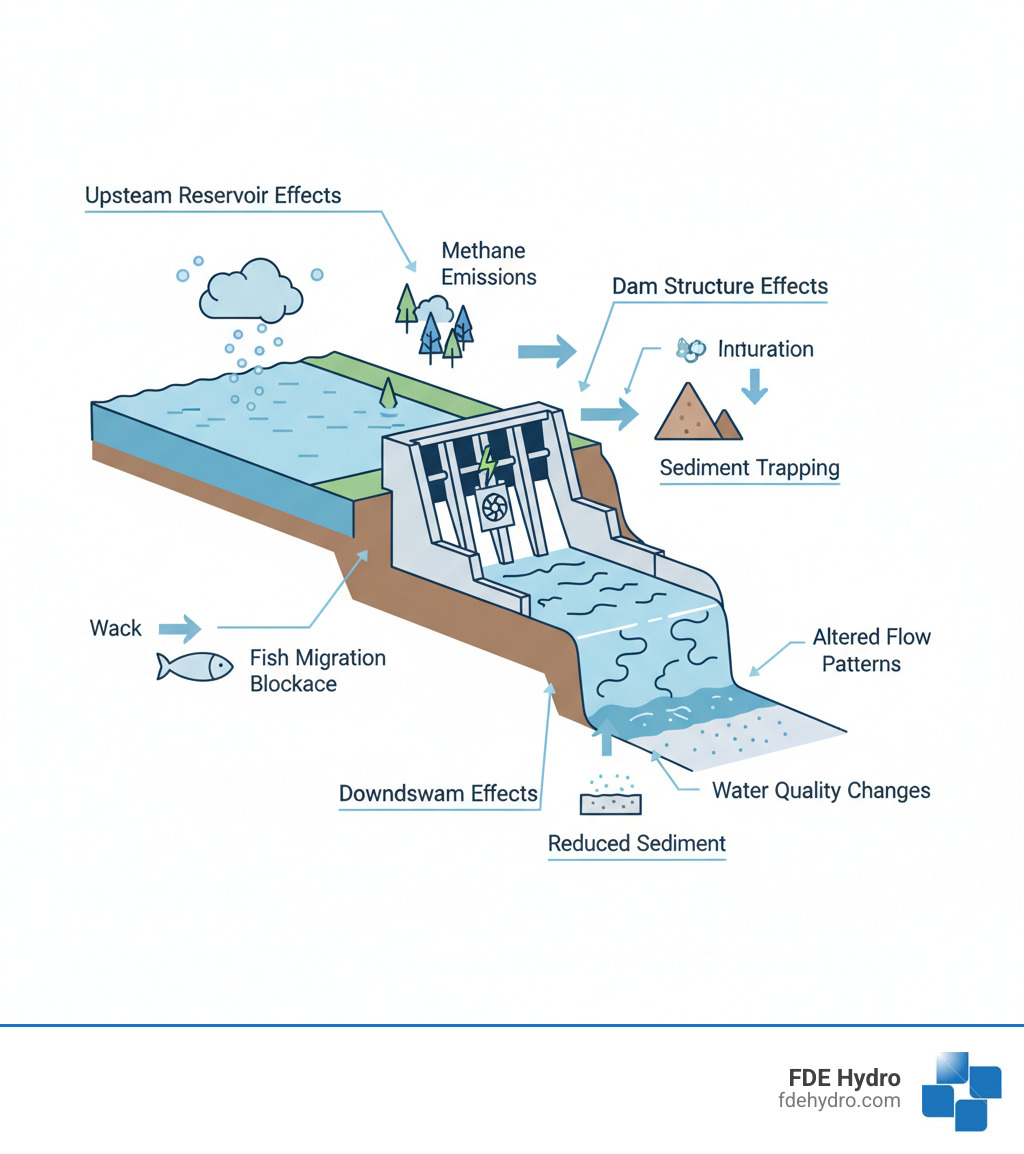

Key Environmental Impacts of Hydropower:

- Ecosystem Disruption: Dams fragment rivers, trap sediments, and alter natural flow patterns.

- Aquatic Life: Fish populations suffer from blocked migration (93% collapse in Europe since 1970) and turbine mortality (5-30% in conventional designs).

- Land Use: Reservoir creation floods habitats and can displace communities, with 28% of planned European projects in protected areas.

- Greenhouse Gases: Decomposing vegetation releases methane and CO2, with emissions varying widely by location (0.01-0.5+ lbs CO2e/kWh).

- Climate Vulnerability: Droughts reduce generation capacity and intensify environmental stress.

Hydropower faces a critical inflection point. As the world transitions from fossil fuels, it remains the largest source of renewable electricity. Yet, its “clean energy” label masks significant environmental consequences that vary dramatically by project design, location, and scale.

The conversation is no longer about whether hydropower is simply “good” or “bad.” Instead, we must understand which types of projects cause what kinds of impacts, and how modern engineering can minimize ecological harm.

This tension is acute for large projects. Over 60% of the world’s long rivers are fragmented by dams, and thousands more are proposed in biodiversity hotspots. In Europe, a million barriers contribute to a 93% decline in migratory fish populations since 1970. Meanwhile, climate change threatens hydropower itself through droughts and altered precipitation.

Fortunately, we can evolve. Emerging technologies—from fish-friendly turbines that reduce mortality to below 2% to run-of-river designs that avoid massive reservoirs—show a better path. Strategic site selection, thoughtful design, and optimized operations can dramatically reduce environmental harm.

As Bill French Sr., founder and CEO of FDE Hydro, I’ve spent decades in heavy civil construction before focusing on modular hydropower solutions that minimize hydropower environmental impact. My work with the Department of Energy’s Water Power Technology Office has reinforced that the future of hydropower depends on balancing clean energy with genuine environmental responsibility.

This guide explores hydropower’s full environmental spectrum—from ecosystem disruption to greenhouse gas emissions—and the practical solutions that can make it truly sustainable. It provides the knowledge needed to make informed decisions that serve both energy needs and environmental health.

The Ecological Footiers: How Hydropower Alters River Ecosystems

Building a hydropower dam places a massive barrier across a river, fundamentally disrupting its natural state. Rivers are dynamic, interconnected systems, and dams reshape the entire landscape, both upstream and downstream. The hydropower environmental impact on river ecosystems begins with this fragmentation.

Upstream, a flowing river becomes a still-water reservoir, favoring lake-dwelling species over native river species. Downstream, the river’s natural ebb and flow are replaced by intermittent releases controlled by energy demands, altering water temperature and flow patterns.

One of the most significant impacts is sediment trapping. Dams block the natural transport of sand, silt, and organic matter that nourishes downstream deltas, beaches, and floodplains. Sediment accumulates behind the dam, reducing reservoir capacity, while downstream areas starve, leading to eroded riverbanks and disappearing coastal wetlands.

How Dams and Reservoirs Affect Aquatic Life

For many aquatic species, dams are an existential threat. They interrupt ancient migration routes for spawning and feeding. The statistics are sobering: in Europe, freshwater migratory fish populations have collapsed by 93% since 1970, with dams being a major cause. Globally, over 60% of long rivers are fragmented, devastating species like salmon and sturgeon whose populations collapse when access to spawning grounds is blocked.

Beyond blockage, the turbines themselves are dangerous. Fish pulled through the massive spinning blades face mortality rates from 5% to 30% in conventional designs due to pressure changes and physical strikes. For a river with multiple dams, these mortality rates compound, decimating populations over time.

Water quality changes add another layer of stress. Deep reservoirs stratify by temperature, and the oxygen-poor bottom layers become zones of decomposition. When dams release this cold, oxygen-depleted water, it can suffocate downstream organisms adapted to warmer, oxygen-rich conditions. These temperature shifts disrupt fish growth, insect life cycles, and entire food webs. Nutrient cycles are also disrupted, which can trigger harmful algal blooms that further deplete oxygen.

The Land Use and Social Hydropower Environmental Impact

Large reservoir projects can transform landscapes on a massive scale, flooding forests, farmland, and entire ecosystems. The Balbina dam in Brazil, for example, flooded 2,360 square kilometers to generate just 250 MW of power—a stark contrast to efficient run-of-river plants that might use a fraction of that land.

The hydropower environmental impact extends to human communities. Large dams often require displacing towns, forcing people from their homes, farmland, and ancestral lands. While our work at FDE Hydro focuses on North America, Brazil, and Europe, the human costs of large dam projects have been documented globally, with some projects displacing tens of thousands of people. Cultural heritage sites can vanish beneath the water, a loss that cannot be easily quantified.

Most concerning is the conflict between hydropower and conservation. In Europe, 28% of all planned hydropower projects are in protected areas—zones designated to preserve critical biodiversity. This tension between renewable energy goals and environmental protection is a central challenge for the industry today.

The Climate Question: Unpacking Hydropower’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Hydropower’s “clean energy” reputation is being re-examined through a life-cycle emissions analysis. While construction emissions are minimal over a dam’s long lifespan, the real issue is the greenhouse gases that can bubble up from the reservoir itself. This comprehensive view has sparked a debate about whether all hydropower deserves its clean energy label.

The surprise came when scientists measured what happens after a reservoir fills. The issue has gained enough attention that researchers are even working on projects to extract dam methane, turning a climate problem into an energy opportunity.

Methane and CO2: The Reservoir Emission Factor

When a valley is flooded, the submerged vegetation and soil decompose. In the oxygen-poor environment at the bottom of a reservoir, this anaerobic decomposition produces both carbon dioxide and methane. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, trapping heat far more effectively than CO2 in the short term. When it bubbles to the surface, it releases a powerful climate-warming gas not typically associated with hydropower.

The amount of gas released varies dramatically by location. Tropical reservoirs are the biggest concern. Warm temperatures accelerate decomposition, and abundant organic matter creates conditions for high emissions. Life-cycle emissions from hydropower in tropical areas can exceed 0.5 pounds of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt-hour.

Temperate reservoirs in cooler climates generally produce fewer emissions due to slower decomposition and less organic matter. Emissions are highest in the first few years after flooding and typically decline over time.

Comparing Hydropower’s Life-Cycle Emissions to Other Energy Sources

When comparing the full life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions, the context of a hydropower project becomes clear.

| Energy Source | Life-Cycle CO2 Equivalent (lbs/kWh) |

|---|---|

| Hydropower (small run-of-river) | 0.01 – 0.03 |

| Hydropower (large, semi-arid) | ~0.06 |

| Hydropower (tropical/peatlands) | >0.5 |

| Natural Gas | 0.6 – 2.0 |

| Coal | 1.4 – 3.6 |

Small run-of-river plants have one of the lowest carbon footprints of any energy source, with emissions as low as 0.01 lbs CO2e/kWh. Large hydro in semi-arid regions also performs well, far better than fossil fuels like natural gas (0.6-2.0 lbs/kWh) and coal (1.4-3.6 lbs/kWh).

However, tropical projects with emissions exceeding 0.5 lbs/kWh begin to approach the impact of natural gas. This means a poorly sited hydropower project could have a larger climate impact than a fossil fuel plant.

This doesn’t mean hydropower is bad—it means location matters enormously. A run-of-river project in a mountain stream has a completely different climate profile than a massive reservoir flooding a tropical rainforest. At FDE Hydro, we focus on innovative approaches like modular precast concrete technology that enable smaller impoundments and run-of-river designs, significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The takeaway is that hydropower’s climate impact is a spectrum. With thoughtful site selection and modern design, it can be one of the lowest-carbon energy sources available. But assuming it’s always “clean” can lead to poor decisions.

A Global Perspective: Hydropower Challenges and Climate Risks

The global boom in dam construction has transformed the world’s rivers, and the cumulative hydropower environmental impact is forcing us to rethink how we plan new projects. When multiple dams are built on the same river, fragmentation accumulates, sediment transport is disrupted, and water quality changes cascade downstream, especially in biodiversity hotspots.

The European Hydropower Dilemma

Europe’s rivers are the most fragmented on the planet, with at least one million barriers contributing to a catastrophic 93% collapse of migratory fish populations since 1970. In response, the WWF and other groups have published a manifesto calling for a halt to new hydropower, arguing that Europe’s potential has been fully harnessed.

The concern is heightened by the proliferation of small hydropower projects. Over 90% of all hydropower plants in Europe are small (under 10 MW), but their collective impact on river fragmentation is devastating—a death by a thousand cuts.

The conflict with conservation is stark: 28% of planned hydropower projects in Europe (33% within the EU) are located in protected areas. This creates a dilemma between pursuing renewable energy targets and honoring environmental commitments.

From my perspective at FDE Hydro, working across North America, Brazil, and Europe, the solution is not to abandon hydropower but to be smarter about it. Our focus on modular, efficient designs allows for more selective project siting, reducing environmental disruption.

The Threat of Climate Change to Hydropower Sustainability

Ironically, the climate change that hydropower helps mitigate now threatens hydropower itself. Hydropower depends on consistent water flow, which is becoming increasingly uncertain due to altered precipitation and prolonged droughts.

The U.S. Southwest is a sobering example, where a 22-year megadrought has dramatically lowered water levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell, severely reducing generation at facilities like the Hoover Dam. When reservoir levels drop, so does power output.

This creates a troubling feedback loop. Reduced water flow means less electricity, making hydropower less reliable. Environmentally, lower water levels lead to higher water temperatures and reduced dissolved oxygen, further stressing aquatic ecosystems. These altered seasonal patterns are not temporary blips; they are fundamental shifts that make it harder to operate facilities in an ecologically responsible way.

Working in places like Kansas and California, I’ve seen how critical resilient and adaptable hydropower solutions are. Climate change demands that we design systems capable of functioning across a wider range of conditions. Acknowledging these vulnerabilities is essential for ensuring hydropower’s long-term sustainability.

The Path to Sustainable Hydropower: Mitigation and Innovation

The challenges of hydropower environmental impact are significant, but we are not stuck with the old ways of doing things. The future of hydropower depends on balancing energy needs with ecological preservation, and innovation is making that balance achievable.

Smart engineering and modern technology can dramatically reduce hydropower’s footprint. At FDE Hydro, our modular precast concrete technology—the “French Dam”—allows for more flexible siting and faster construction. Initiatives like the U.S. Department of Energy’s Hydropower Technology Development program are also pioneering solutions being implemented in North America, Brazil, and Europe.

Large Dams vs. Run-of-River: A Key Distinction for Hydropower Environmental Impact

The type of facility is critical. Large dams with reservoirs provide consistent power and flood control but come at a high environmental cost: massive land use, river fragmentation, blocked sediment, and, in the tropics, significant methane emissions. In contrast, run-of-river projects divert a portion of the river’s flow, maintaining more of its natural character. Their footprint is tiny by comparison—a 10 MW plant might use just 2.5 acres—and their emissions are among the lowest of any energy source (0.01-0.03 lbs CO2e/kWh). While their power generation fluctuates with river flow, run-of-river designs generally offer a significantly lower environmental impact.

Technological Solutions for Mitigating the Hydropower Environmental Impact

Innovation is providing powerful tools to address key environmental concerns:

- Fish-friendly turbines: New advanced designs prioritize smoother water passage and slower blade speeds, aiming to reduce fish mortality from over 15% in conventional turbines to 2% or less.

- Advanced fish passage systems: Beyond simple ladders, solutions now include trap-and-haul systems, elevators like the one at Safe Harbor Dam, and even pressurized “salmon cannons” to help migratory species bypass obstacles.

- Sediment management: Techniques like sluicing during high flows or constructing bypass tunnels help move vital sediment downstream, maintaining habitats and reservoir capacity.

- Environmental flow simulation: Operational models can mimic a river’s natural rhythms, controlling water releases to support downstream ecosystems and aquatic life.

The Importance of Strategic Siting, Design, and Operation

Technology is most effective as part of a comprehensive strategy. The most sustainable projects combine smart planning, design, and operation from the start.

Strategic site selection is paramount. Using system-scale planning to avoid sensitive ecosystems and critical migratory corridors prevents irreversible damage. This is often paired with retrofitting existing dams with modern technology, which is more efficient than new construction. Finally, adaptive operational adjustments using real-time data and AI can optimize water releases for ecological health. In some cases, dam removal of outdated structures is the best solution for restoring a river.

Our modular precast concrete technology at FDE Hydro supports this strategy by offering more flexibility in siting and design. The path forward is about making smarter choices: choosing the right technology for the right location and operating facilities in ways that respect ecological needs. These are the foundations of truly sustainable hydropower.

Conclusion

The hydropower environmental impact is complex. It offers valuable renewable energy but can fragment rivers, harm fish, and even release greenhouse gases. The question is not whether these impacts exist, but how we address them. Fortunately, we are not stuck with the methods of the past. Modern solutions—from fish-friendly turbines and run-of-river designs to strategic site selection—are making sustainable hydropower achievable.

The future of hydropower depends on our willingness to accept these innovations and evaluate each project on its own merits. A tropical reservoir and a small run-of-river plant have vastly different ecological footprints.

At FDE Hydro, we’ve built our approach around this principle. Our patented modular precast concrete technology—the “French Dam”—enables faster, more cost-effective, and responsible construction and retrofitting of hydropower infrastructure across North America, Brazil, and Europe. Our designs prioritize flexibility, allowing projects to adapt to their specific ecological contexts and minimize disruption.

My decades in heavy civil construction and work with the Department of Energy’s Water Power Technology Office have shown me that we don’t have to choose between energy and the environment. With innovation, strategic planning, and a commitment to stewardship, we can design systems where both can thrive.

The technology and knowledge exist. It is up to us to apply them with wisdom and care.

Learn more about our innovative water control systems