What is Hydroelectric Power Generation?

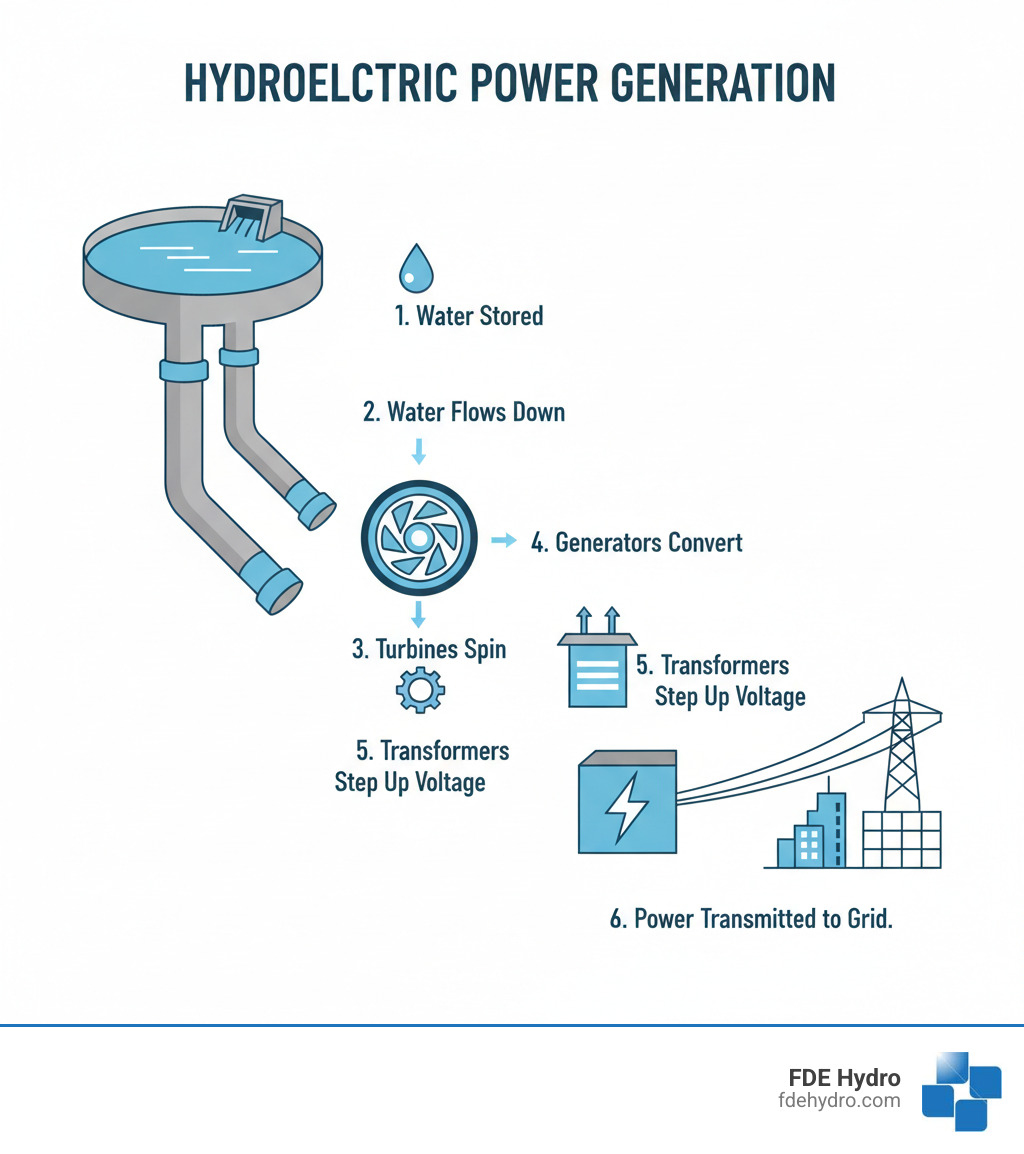

Hydroelectric power generation is the process of producing electricity by using the energy of flowing or falling water. Here’s how it works:

- Water is stored behind a dam in a reservoir at a higher elevation

- Water flows down through large pipes called penstocks, building pressure

- The moving water spins turbines connected to generators

- Generators convert the mechanical energy into electrical energy

- Electricity flows through transformers and power lines to homes and businesses

Hydropower is a renewable energy source because it relies on the water cycle—evaporation, precipitation, and runoff—which constantly replenishes the water supply. Unlike fossil fuels, it produces no direct carbon emissions during operation.

For over two thousand years, humans have harnessed water power, from ancient Greek waterwheels grinding grain to today’s massive dams generating electricity for millions. Hydropower now supplies 15% of the world’s electricity and represents the largest source of renewable energy globally, with nearly 1,400 GW of installed capacity as of 2021.

The appeal is straightforward: water flows predictably, hydropower plants can ramp up or down quickly to meet demand, and once built, they operate with minimal fuel costs for 65 to 85 years. Yet hydropower also presents challenges—high upfront construction costs, long development timelines, and environmental impacts that require careful management.

I’m Bill French, founder and CEO of FDE Hydro, and I’ve spent the past decade developing modular construction solutions for hydroelectric power generation after leading major civil construction projects for five decades. In 2015, I was selected by the Department of Energy to help define the strategic roadmap for next-generation hydropower solutions in the United States.

The Mechanics of Hydroelectric Power Generation

Hydroelectric power generation is really just physics doing what it does best—converting one form of energy into another. It starts with water sitting peacefully in a reservoir, high above the power plant. That water has what scientists call potential energy, which is just a fancy way of saying it has stored energy because of its height.

When we release that water, gravity pulls it downward, and all that potential energy transforms into kinetic energy—the energy of motion. The water picks up speed as it rushes down through massive pipes. Our job is to capture that moving energy and turn it into electricity.

Think of it like this: imagine holding a bowling ball at the top of a staircase. It’s not doing anything yet, but it has the potential to do a lot. Drop it, and gravity takes over, converting that potential into motion. The higher the staircase and the heavier the ball, the more energy you get. That’s exactly how hydropower works, except we’re talking about millions of gallons of water falling from great heights.

This is why geography matters so much. A river dropping sharply through mountains? Perfect for hydropower. A gently meandering river across the plains of Kansas? Not so much. We need what engineers call “head”—the vertical distance the water falls—and plenty of water flow to make hydroelectric power generation work efficiently.

For a deeper look at these fundamentals, the Department of Energy has an excellent resource on How Hydropower Works.

What are the main components of a hydroelectric power plant?

A hydroelectric power plant is like a well-orchestrated machine, with each part playing a specific role in turning water into watts. Let’s walk through these components as water would experience them on its journey to becoming electricity.

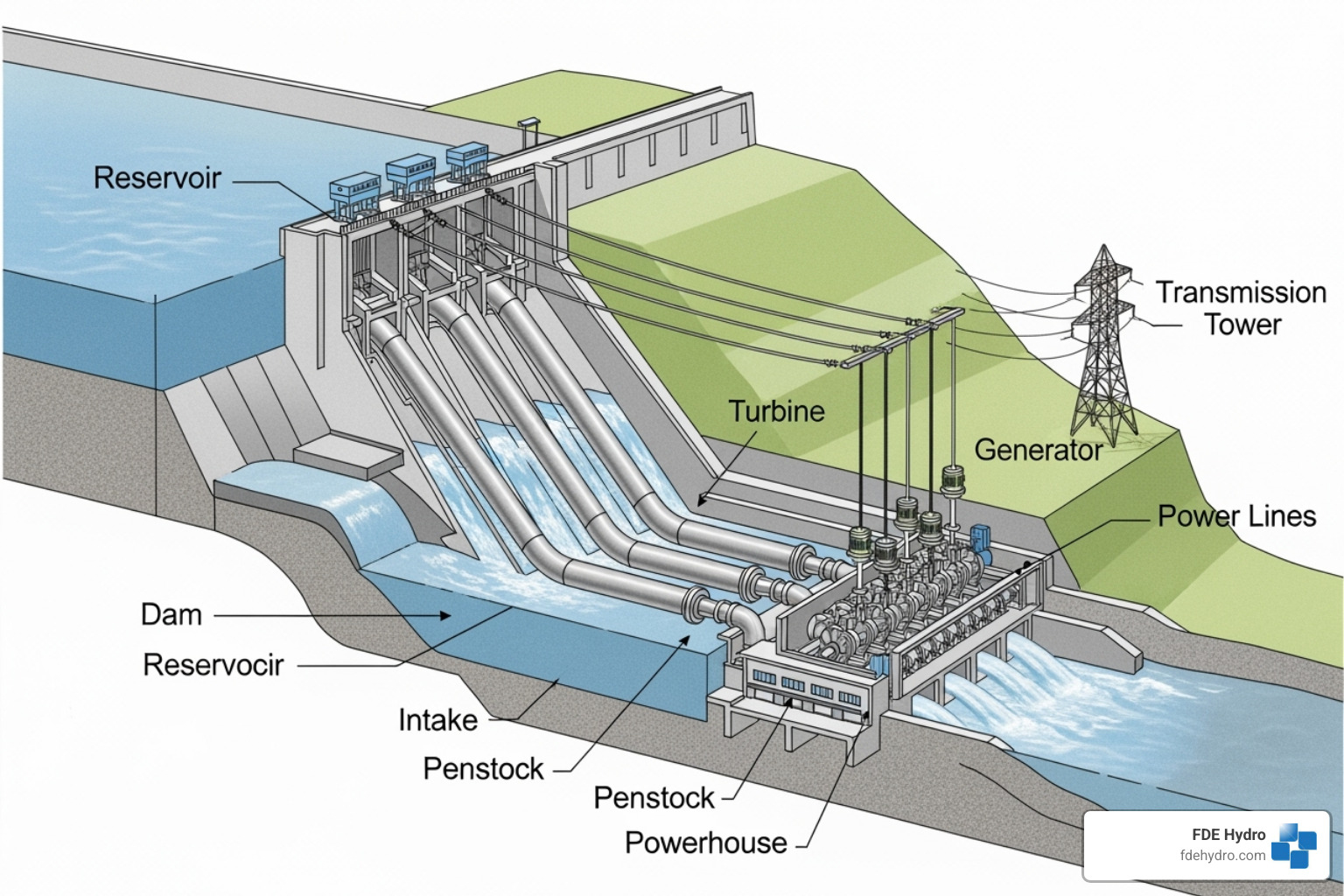

Everything begins with the dam—the massive barrier stretching across a river valley. These structures can be enormous concrete monuments like the Hoover Dam, or smaller diversion weirs, but they all serve the same purpose: holding back water and creating the elevation difference we need.

Behind the dam sits the reservoir, which is essentially a giant battery made of water. This artificial lake stores tremendous amounts of water—up to 1,500 terawatt-hours of potential electrical energy when you add up all the conventional hydropower reservoirs worldwide. Beyond power generation, these reservoirs often provide flood control, drinking water, and recreation opportunities.

When it’s time to generate electricity, water enters through the intake, a carefully designed gate structure that controls how much water flows into the system. From there, it rushes into the penstock—those enormous steel or concrete pipes you might have seen running down the face of a dam. These penstocks channel the water at high pressure toward the power plant below.

At the bottom, the pressurized water slams into the turbine, a precisely engineered wheel with curved blades. The water’s force spins the turbine at high speed, and this is where we finally convert water’s kinetic energy into mechanical rotation. Different turbine designs—Francis, Pelton, and Kaplan are the main types—work best under different conditions of water flow and head.

The spinning turbine connects directly to a generator through a shaft. This is where mechanical energy becomes electrical energy through a process we’ll explain in just a moment. The electricity comes out at a relatively low voltage, so transformers step it up to the high voltages needed for efficient long-distance transmission through power lines to homes and businesses.

Finally, the water that’s done its job flows away through the tailrace, a channel that returns it to the river downstream. The water continues on its natural journey, ready to be used again as the water cycle continues.

How do turbines and generators create electricity?

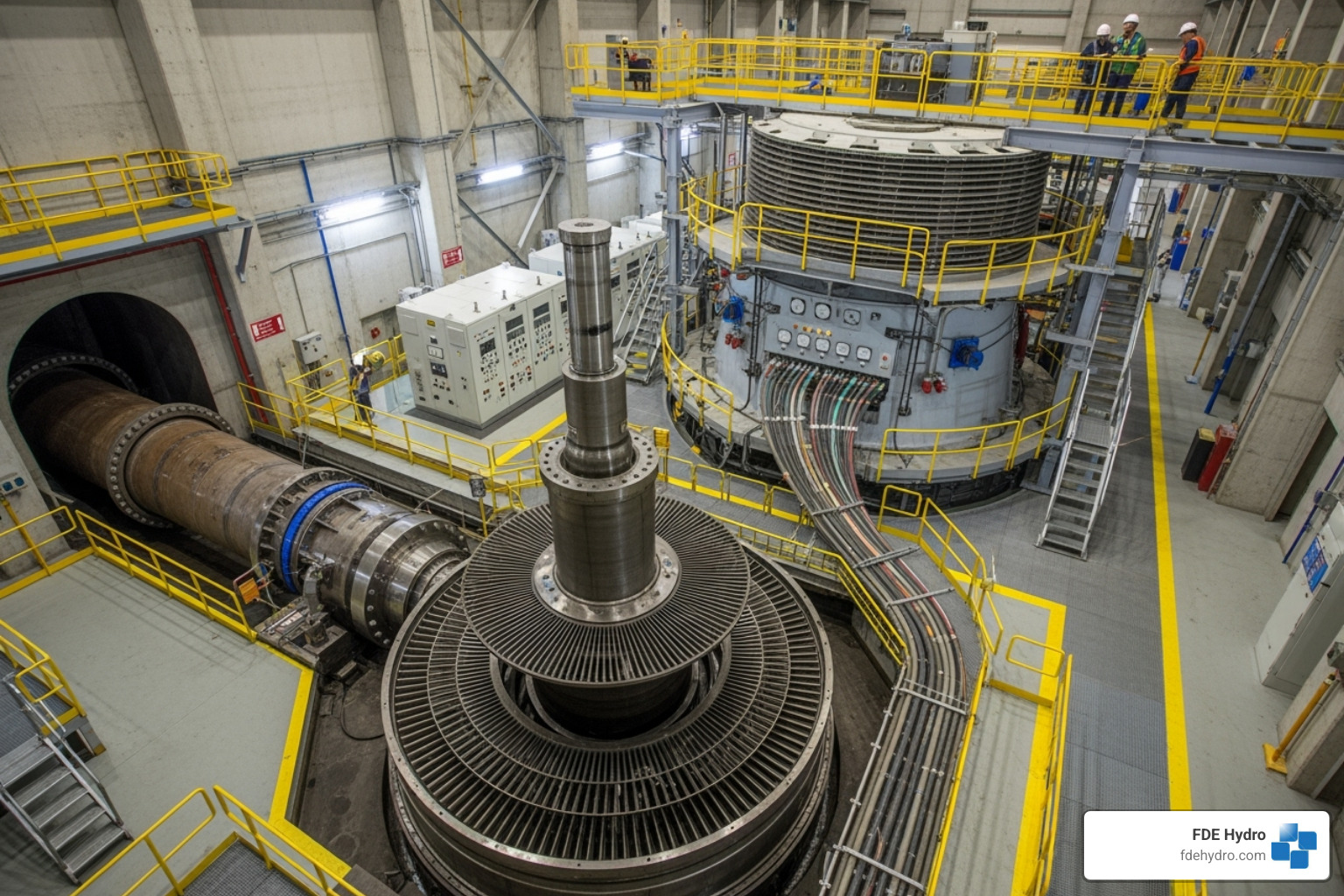

Here’s where water’s journey reaches its climax. When that high-pressure water hits the turbine blades, it strikes with tremendous force—enough to spin multi-ton turbines at hundreds of revolutions per minute. Each blade is carefully shaped to extract the maximum energy from the flowing water.

The turbine connects by a shaft to the generator, and this is where Michael Faraday’s findy from the 1830s comes into play. Faraday figured out that moving a magnet near a wire creates an electric current in that wire. It’s called electromagnetic induction, and it’s the principle behind every generator in the world.

Inside a hydroelectric generator, powerful electromagnets are mounted on a spinning part called the rotor. As the turbine spins, it rotates these magnets past coils of copper wire arranged in the stationary outer shell—the stator. The moving magnetic field induces an alternating current (AC) in those copper coils, and that’s our electricity.

It’s remarkably neat when you think about it. Water falls, spins a wheel, rotates some magnets past some wire, and suddenly you’ve got the power to run a city. The U.S. Geological Survey – Hydroelectric Power: How it Works offers a detailed explanation if you want to dig deeper into the science.

What is Pumped Storage Hydroelectricity?

Not all hydroelectric power generation involves a river flowing through a dam. Some of the most valuable hydropower facilities actually pump water uphill—which sounds backwards until you understand what they’re really doing.

Pumped storage hydroelectricity works like a giant rechargeable battery, except it uses water and gravity instead of chemicals. These systems have two reservoirs at different elevations—one up high, one down low. During times when electricity is cheap and abundant (like 2 AM when everyone’s asleep, or midday when solar panels are cranking out more power than anyone needs), the facility uses that excess electricity to pump water from the lower reservoir to the upper one.

That water sitting in the upper reservoir is now stored energy, just waiting to be released. When electricity demand spikes—say, when everyone comes home on a hot summer evening and turns on their air conditioners—the plant releases that stored water. It rushes downhill through penstocks, spins turbines, and generates electricity within minutes.

This ability to respond instantly makes pumped storage hydroelectricity incredibly valuable for grid stability. In fact, pumped storage provides 96% of all utility-scale energy storage in the United States. When wind suddenly dies down or clouds pass over solar farms, pumped storage facilities can fill the gap before anyone notices a flicker in their lights.

Yes, these facilities use more electricity pumping water uphill than they generate on the way down—they’re net energy consumers. But that’s missing the point. Their real value is in storing energy when it’s abundant and releasing it when it’s desperately needed. They’re the grid’s insurance policy, keeping everything stable and allowing us to integrate more intermittent renewable sources like wind and solar.

Learn more about this critical technology on our Pumped Storage Hydropower page.

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Hydropower

When we consider hydroelectric power generation, it’s important to approach it with a balanced perspective. Like any large-scale energy technology, it comes with a unique set of advantages that make it an invaluable part of our energy mix, as well as disadvantages and environmental trade-offs that demand careful consideration and ongoing innovation.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Renewable & Clean: Produces no direct air pollution and relies on the natural water cycle. | High Initial Cost: Building large dams requires a massive upfront investment and long development timelines. |

| Low Operating Costs & Long Lifespan: Once built, plants can operate for 65-85 years or more with minimal fuel and maintenance costs. | Environmental Impact: Dams can alter river ecosystems, block fish migration, and change water temperature and sediment flow. |

| Grid Flexibility & Reliability: Hydropower can be ramped up or down in minutes, providing essential stability to the power grid. | Human Displacement: The creation of large reservoirs can require relocating entire communities. |

| Multiple Benefits: Reservoirs can provide flood control, a reliable water supply for irrigation and cities, and recreational opportunities. | Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Decomposing organic matter in reservoirs can release methane, a potent greenhouse gas. |