Why Dam Flood Control Matters to Lives, Economies, and Infrastructure

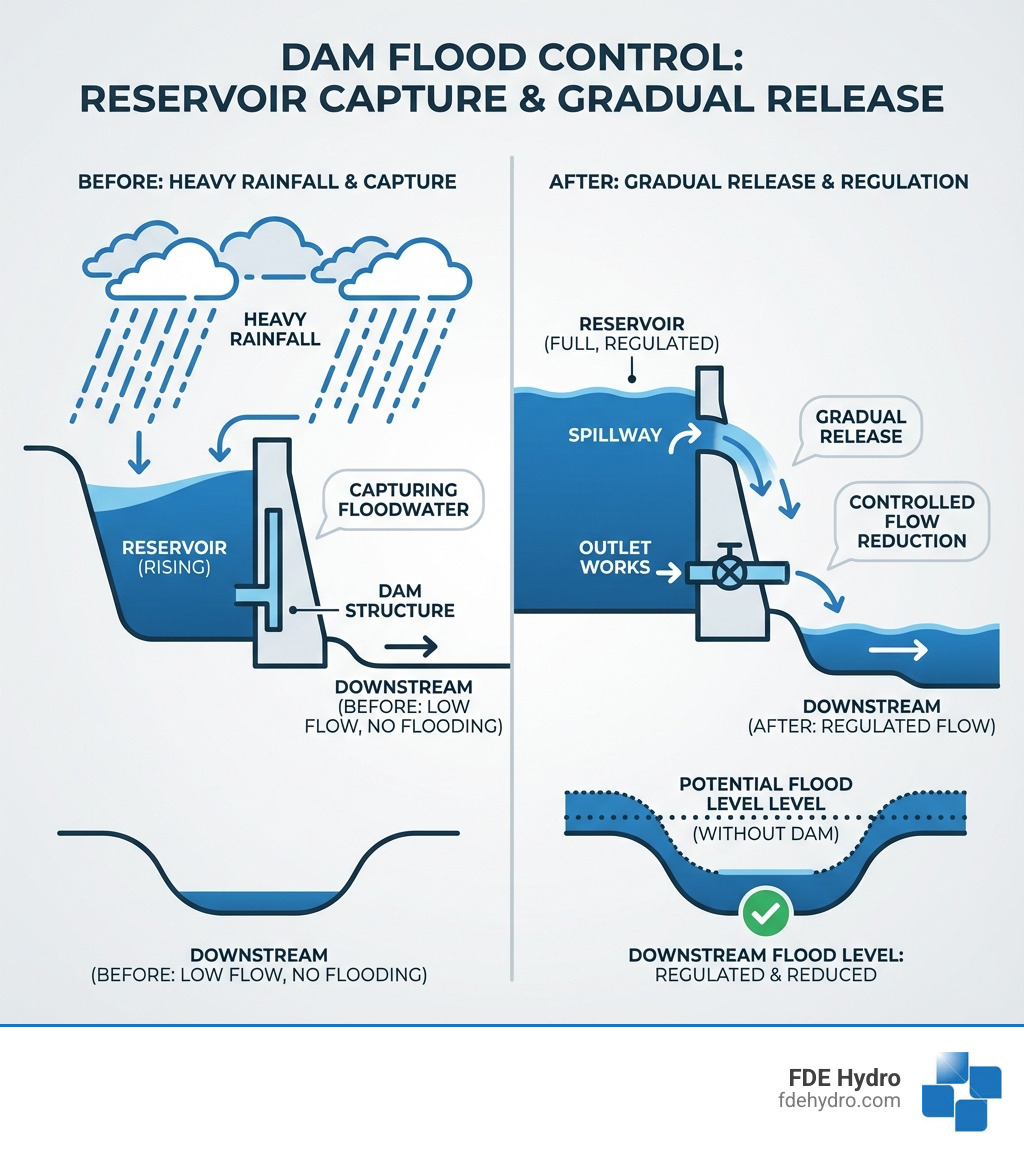

Dam flood control refers to the strategic use of dams and reservoirs to capture, store, and regulate excess water during flood events, reducing downstream damage to communities and infrastructure. Here’s how it works:

Key Functions of Dam Flood Control:

- Water Storage – Reservoirs capture floodwaters before they can overwhelm downstream areas

- Flow Regulation – Controlled release of water reduces peak flow and extends flood duration

- Peak Reduction – Dams can reduce flood peaks by 12-22%, saving approximately $53-96 billion annually in GDP losses

- Multi-Purpose Operation – Balances flood control with water supply, hydropower, and recreation

Flooding has emerged as one of the most impactful disasters of our time. Nearly two billion people live in areas prone to high flood risk, with 660 million in urban regions exposed to river flooding. In the United States alone, the 1993 Mississippi River flood killed 50 people and caused $12 billion in damage. Around the world—from Southeast Asia to Australia to Venezuela—communities face this threat every year, made worse by changing precipitation patterns from global warming.

Dams stand as a cornerstone of modern flood management. They don’t just block water—they actively manage it. By storing floodwaters in reservoirs and releasing them in a controlled manner over time, dams lengthen the passage of floods and reduce peak flows that would otherwise devastate communities, farmland, and critical infrastructure downstream.

But dam flood control isn’t simple. These massive structures must balance competing demands: protecting against floods while supplying drinking water, generating clean hydroelectric power, supporting recreation, and sustaining ecosystems. The engineering challenges are immense. The economic stakes are enormous. And the consequences of failure can be catastrophic—during the twentieth century, more than 8,000 people perished in over 200 dam failures.

As the founder and CEO of FDE Hydro™, I’ve spent decades developing innovative solutions for water infrastructure, like modular civil construction methods that revolutionize dam flood control. My experience in heavy civil construction and strategic planning for next-generation hydropower has given me deep insight into the critical importance and complex challenges of dam-based flood management.

In this guide, we’ll walk through how dam flood control actually works—from the basic anatomy of these structures to the sophisticated operations that keep communities safe. We’ll examine the economics, the environmental trade-offs, the risks, and the innovations that are shaping the future of flood management.

Common Dam flood control vocab:

The Anatomy of Flood Control Structures

When we talk about managing water, it’s easy to confuse the various structures involved. Let’s start by clarifying the fundamental differences between the main players in flood defense: dams, dikes, and levees.

Dams vs. Dikes

The primary difference between dikes and dams in flood control lies in their orientation and purpose. Think of it this way:

- Dikes run parallel to a body of water, like a river or coastline. Their main job is to keep water away from land. They act as continuous barriers, protecting low-lying areas from encroaching water. Beyond flood prevention, dikes are also used for land reclamation and shoreline protection.

- Dams are built perpendicular across a river or waterway. Their purpose is to hold back water, creating a reservoir upstream, and to control its flow downstream. Dams are the ultimate multitaskers, serving not only for dam flood control but also for water storage, hydroelectric power generation, and even recreation.

Levees & Flood Walls

Levees are essentially man-made embankments, typically made of earth, built along the banks of a river or other body of water. Much like dikes, their function is to prevent water from overflowing its natural banks and inundating adjacent land. Flood walls, on the other hand, are often concrete or masonry structures, used in urban areas where space is limited, providing a rigid barrier against rising waters.

These local flood protection works create a physical barrier whose effectiveness relies on continuous maintenance by local agencies. This includes promoting sod growth to prevent erosion, removing burrowing animals, and regular mowing. Crucial inspections check for settlement, seepage, and clear drainage systems, ensuring the structures are always ready to divert floodwaters. You can learn more about these structures by visiting our guide on Water Control Structures.

Here’s a quick comparison:

| Structure | Function | Orientation | Primary Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dam | Stores and regulates water flow | Perpendicular across waterway | Flood control, water storage, hydropower, recreation |

| Dike | Blocks water from entering land | Parallel to water body | Flood prevention, land reclamation, shoreline protection |

| Levee | Blocks water from river overflow | Parallel to river bank | Local flood protection, prevents inundation of adjacent land |

Dam Construction Materials and Key Components

The materials we choose for dam construction are crucial, influencing a dam’s strength, longevity, and suitability for different environments.

Construction Materials

Dams are generally constructed from three basic materials: earth, rocks, and concrete.

- Earthen Dams: These are the most common type, making up about 80% of all dams in the United States and Canada. They are practical and often inexpensive to build, especially in broad valleys, using locally available soil and clay.

- Rockfill Dams: These dams use compacted rock for their main structure, often with an impervious core (like clay) or a watertight membrane (like concrete or asphalt) on the upstream face to prevent seepage.

- Concrete Dams: These are massive structures, typically anchored to solid bedrock. There are several types:

- Gravity Dams: Rely on their sheer bulk and weight to resist the water’s pressure. They can often remain stable even if floodwaters overtop them.

- Buttress Dams: Use a series of supporting buttresses to transfer the water load to the foundation, often lighter than gravity dams.

- Arch Dams: Curved structures that transfer the water’s pressure horizontally to the valley walls. They are often less expensive to build than gravity dams but can be more vulnerable to localized failures.

At FDE Hydro, we’re pushing the boundaries of concrete dam technology with our innovative modular precast concrete systems, sometimes referred to as “French Dam” technology. This approach significantly reduces construction costs and time for new and retrofitted hydroelectric dams and water control systems in North America, Brazil, and Europe. Our advanced methods ensure robust and resilient structures. You can explore more about these techniques in our article on Dam Construction Methods.

Essential Components

Beyond the main structure, several essential components ensure a dam functions effectively for flood control:

- Outlet Works: These are gates or conduits, typically located near the base of the dam, designed to discharge normal low-water flow. They allow operators to control the rate at which water is released from the reservoir, a critical function for managing downstream river levels and mitigating flood impacts.

- Spillways: Often called the “safety valves” of a dam, spillways are generally broad, reinforced channels (or sometimes tunnels) that allow excess water to escape harmlessly when the reservoir reaches a certain level. This prevents water from overtopping the dam itself, which could lead to catastrophic failure. Modern spillways are carefully designed to convey the maximum probable flood safely. We dig deeper into their importance in our dedicated piece on Spillways.

These components, along with many others, work in concert to make up the complex systems that are modern dams. For a comprehensive look, check out our Hydroelectric Dam Components Ultimate Guide.

How Dams Actively Manage and Mitigate Floodwaters

Dams are far more than just static barriers; they are dynamic tools in our fight against flooding.

Beyond Storage

How do dams contribute to flood control beyond just storing water? The magic lies in their ability to actively manage water. During heavy rainfall or snowmelt, a dam’s reservoir captures the sudden influx of water. Instead of allowing this surge to rush downstream and cause immediate devastation, the dam holds it back. Then, operators can release the stored water gradually, at a controlled rate, over an extended period. This controlled release is fundamental to dam flood control.

Regulating Flow

By regulating the flow, dams perform a crucial service: they lengthen the flood passage time and significantly reduce the peak flow of a flood event. Imagine a bathtub overflowing versus slowly draining; the latter is what dams achieve. This careful management allows downstream areas more time to prepare, evacuate, and protect property, while simultaneously reducing the destructive power of the water itself.

Reducing Peak Flow

The impact of this peak reduction is substantial. Studies show that the flood control function of dams can reduce the GDP at risk from flooding by an impressive 12-22%. This translates to an approximate annual savings of USD 53-96 billion globally. In Myanmar, dams have contributed to a 50% reduction in flood damages to buildings and assets, while the Soyanggang Dam in South Korea boasts a 68% success rate in reducing flood losses. These numbers highlight the tangible economic benefits of strategic dam flood control.

Integrated Programs

Often, dams aren’t the sole answer; they are part of a larger, integrated flood-control program. These programs combine various measures to offer comprehensive protection. They might involve:

- Levees and Flood Walls: As discussed, these local barriers protect specific areas.

- Floodways: These are designated diversion channels designed to carry excess water away from vulnerable areas, often bypassing urban centers.

- Channel Modifications (Channelization): This involves deliberately rerouting a stream or artificially modifying its channel by straightening, deepening, widening, clearing, or lining it. The goal is to increase the water’s flow velocity and capacity, moving floodwaters through an area more quickly. However, channelization can have drawbacks, such as increased erosion and downstream hazards, so it’s a tool used with careful consideration.

The Mississippi River Project in the United States is a historic example of such an integrated approach, evolving significantly after major floods like the disastrous one in 1927. It incorporated extensive levee systems, dams, reservoirs, bank stabilization, and floodways to manage the mighty river.

The Balancing Act of Multi-Purpose Dam Flood Control

One of the most complex aspects of dam flood control is managing multi-purpose reservoirs. Our dams are rarely built for a single purpose. They are often designed to serve many masters: flood control, water supply for drinking and irrigation, hydroelectric power generation, and recreation. And here’s where the fun begins, or rather, the challenging balancing act.

Competing Needs

Consider the inherent conflicts:

- Flood Control: For effective flood control, a reservoir needs to have ample storage space available, meaning it should ideally be kept relatively low or even empty before a flood season.

- Water Supply: For irrigation or domestic use, we want the reservoir to be as full as possible, holding onto every drop.

- Hydroelectric Power Generation: Power production is most efficient when the reservoir is kept full, ensuring maximum “head” (the height difference between the water surface and the turbines).

- Recreation: Stable water levels are best for boating, fishing, and maintaining fish and wildlife habitats.

These competing needs make the management of multi-purpose reservoirs a very complicated enterprise. We can’t always satisfy all demands simultaneously. For example, maximizing electricity generation might conflict with the need to lower reservoir levels strategically before a flood season to create storage capacity. However, different purposes of dams can be complementary. Strategic lowering of reservoir levels before the flood season, combined with meticulous control of water discharge, can prevent spillover and minimize flood magnitude while still supporting power generation over time. This concept of shared water uses is critical for sustainable reservoir management, as highlighted in scientific research on the SHARE concept for multipurpose reservoirs.

Operational & Maintenance Duties

The responsibility for managing these complex systems is immense. Operational and maintenance duties are continuous and demanding, typically handled by local agencies in coordination with federal bodies like the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). A designated superintendent oversees all structures, ensuring daily checks, frequent inspections, and regular maintenance. Mandated reporting on reservoir levels, gate operations, and other key data becomes even more frequent during flood events, ensuring our flood control systems are always ready.

The Economics, Environment, and Risks of Dam Flood Control

While dams offer immense benefits, we must also acknowledge their economic, environmental, and social trade-offs.

Economic Benefits

The economic benefits of effective dam flood control are significant and far-reaching. As we’ve seen, dams can reduce the GDP at risk from flooding by 12-22%, translating to annual savings of USD 53-96 billion. This mitigation prevents direct and indirect economic losses, such as damage to infrastructure, inventory loss for businesses, and disruptions to production. Our modular construction methods for dams are designed to reduce upfront Hydropower Project Costs, making these vital flood control projects more economically viable and bringing these savings within reach for more communities.

Environmental & Social Costs

However, the construction and operation of dams are not without their disadvantages:

- Sedimentation and Erosion: Dams trap sediment, which can reduce reservoir capacity over time. Downstream, the water released from dams is sediment-starved, leading to increased erosion of riverbeds and banks. This loss of sediment can even contribute to coastal erosion, as deltas no longer receive the natural replenishment they need.

- Habitat Disruption: Dams significantly alter natural river ecosystems. They change water quality—temperature, salinity, and nutrient content—which can negatively impact aquatic life. Migratory fish species, like salmon, often struggle to pass dams, even with the aid of fish ladders, which are expensive and only partially effective.

- Community Relocation: Large dam projects often require the inundation of vast areas, leading to the loss of valuable farmland and the displacement of communities. The Three Gorges Dam in China, for instance, cost $24 billion and required relocating over 1 million people, highlighting the profound social costs of dam planning. For a deeper understanding of these complex issues, the World Commission on Dams final report on development framework provides extensive insights.

Dam Safety, Failure, and the Challenge of Climate Change

The safety of dams is paramount, as the consequences of failure can be catastrophic.

Dam Safety

What are the key considerations for dam safety and the potential consequences of dam failure? Historically, dam failures have been tragic. During the twentieth century alone, over 8,000 people perished in more than 200 dam breaks. The Johnstown Flood of 1889, caused by the failure of an earthen dam, killed 2,209 people—a stark reminder of the potential for devastation.

The main causes of dam failures associated with hydrologic conditions include:

- Overtopping: The dam being overwhelmed by floodwaters due to inadequate spillway capacity.

- Internal Structural Failure: Particularly in earthen dams, this can involve seepage and erosion within the dam body.

- Failure of the Dam Foundation: Issues with the underlying geology can compromise the entire structure.

To mitigate these risks, rigorous guidelines are in place. The Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety provide thorough procedures for selecting and accommodating Inflow Design Floods (IDFs), which are the flood levels a dam is designed to safely withstand. Our modular precast concrete dam technology, with its inherent structural integrity and rapid construction, contributes to improved dam safety and resilience, particularly in regions like North America, Brazil, and Europe where we operate.

Climate Change Impact

How does climate change impact the effectiveness and necessity of dams for flood control? This is a question that weighs heavily on us all. Climate change is bringing increased precipitation and more extreme weather events, leading to higher Probable Maximum Precipitation (PMP) values and, consequently, more frequent and severe floods. This means that dams designed decades ago may no longer be adequate for the new hydrological realities.

The impact is twofold:

- Effectiveness: Existing dams may need to be re-evaluated and potentially upgraded to handle larger, more intense flood events than they were originally designed for. This is a massive undertaking for aging infrastructure.

- Necessity: The increasing frequency and intensity of floods underscore the critical and growing necessity for robust dam flood control measures. Dams, and the innovation in their design and construction, become even more vital tools in protecting communities from the escalating threats of climate change. Indeed, we believe that The Biggest Untapped Solution to Climate Change is in the Water.

Governance and Modern Innovations in Flood Management

Beyond the physical structures, effective dam flood control requires smart policies and continuous innovation.

Preventing Floodplain Misuse

One of the best ways to avoid the economic, social, and environmental disadvantages associated with flood control systems is to prevent floodplain misuse. We sometimes mistakenly believe that “flood control” offers absolute protection, leading to dangerous development in floodplains. Effective strategies include:

- Flood Zoning Laws: Restricting certain types of development in high-risk flood-hazard areas.

- Building Codes: Mandating flood-resistant construction for any development allowed in flood-prone zones.

- Flood Insurance: Providing financial protection while also discouraging risky development through higher premiums in high-risk areas.

Additionally, we can encourage appropriate uses for flood hazard zones, such as open spaces, parks, or agriculture. For existing structures, flood-proofing or relocation can be viable options. Land-treatment procedures like reforestation, terracing, and contour ditches can improve natural water retention upstream. In urban areas, innovative solutions like rooftop or underground water retention tanks and porous pavements help manage stormwater runoff locally.

Modern Temporary Solutions

While permanent dams are crucial, temporary flood control solutions have also seen significant advancements. How do modern temporary flood control solutions like AquaDam and TrapBag compare to traditional methods?

- AquaDam: These are water-filled barriers that literally “use water to control water.” Made of durable materials like virgin-resin polyethylene and polypropylene, AquaDams are quick to install and remove, cost-effective, and environmentally conscious. They are excellent for temporary cofferdams in construction, residential flood protection, and municipal emergency response.

- TrapBag: These are modular cellular barriers designed with 60% of their mass concentrated in the lower half for exceptional stability. They can be rapidly filled with sand, gravel, or small rocks using heavy machinery, making them ideal for quickly forming emergency dikes or temporary wall dams.

Compared to traditional methods like sandbags, earth-filled barriers, or steel sheetpiles, these modern solutions offer less labor, faster deployment, cleaner operation, and greater flexibility. Our own expertise in Modular Dam Construction aligns with this trend, emphasizing speed, efficiency, and adaptability for more permanent water infrastructure.

Regulatory Frameworks for Dam Flood Control

Effective dam flood control relies on robust regulatory frameworks. What are the regulatory frameworks governing flood control structures, such as those managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers?

In the United States, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) plays a central role. They prescribe regulations for the use of storage allocated for flood control and navigation in federally constructed reservoirs. These regulations, found in documents like 33 CFR Part 208 — Flood Control Regulations, outline the responsibilities of local agencies for maintenance and operation, reporting requirements, and operational procedures for specific dams and reservoirs.

Key concepts within these frameworks include:

- Inflow Design Flood (IDF): This is the flood flow level that a dam is designed to accommodate. It’s determined by evaluating the potential consequences of a dam failure. The IDF is the flood above which any incremental increase in downstream water surface elevation due to dam failure is no longer considered an unacceptable additional threat.

- Probable Maximum Flood (PMF): For dams with a high hazard potential (where failure would likely cause loss of human life), the PMF is often the standard IDF. The PMF represents the most severe combination of meteorological and hydrological conditions reasonably possible in a drainage basin.

These regulations ensure that dams are designed, operated, and maintained to the highest safety standards, protecting lives and property across our operating regions in North America.

Frequently Asked Questions about Dam Flood Control

What is the primary difference between a dam and a levee?

A dam is built across a waterway to impound water, creating a reservoir for storage and regulating downstream flow, often for flood control, power generation, or water supply. A levee, on the other hand, is an embankment built parallel to a river or coastline, primarily to prevent water from overflowing its banks and inundating adjacent land. We can think of a dam as controlling the water source, while a levee controls the water’s spread.

How do multi-purpose dams balance flood control with power generation?

Balancing flood control and power generation in multi-purpose dams is a delicate dance. For flood control, we ideally want an empty reservoir to capture incoming floodwaters. For power generation, we want a full reservoir to maximize the water head for turbines. The balance is achieved through careful operational planning, often involving:

- Seasonal Drawdowns: Strategically lowering reservoir levels before anticipated flood seasons (e.g., spring thaw or hurricane season) to create flood storage capacity.

- Weather Forecasting: Utilizing advanced meteorological data to predict rainfall and adjust reservoir releases accordingly.

- Controlled Releases: Managing the outflow of water to reduce downstream flood peaks while still generating power when possible, or prioritizing flood control during extreme events.

- Coordination: Close cooperation among various stakeholders, including flood control agencies, power utilities, and water supply managers, to make real-time decisions.

What are the biggest risks associated with using dams for flood control?

While dams are invaluable for flood control, we must be aware of the inherent risks:

- Dam Failure: The most catastrophic risk, often caused by inadequate spillway capacity (leading to overtopping), structural weaknesses, or foundation issues. A failure can lead to immense loss of life and property downstream.

- Environmental Impacts: Dams can significantly alter ecosystems, causing sedimentation in reservoirs, erosion downstream, changes in water quality, and disruption of aquatic habitats and fish migration.

- Social Disruption: Large dam projects can necessitate the relocation of communities and the loss of valuable agricultural land.

- False Sense of Security: The term “flood control” can sometimes lead to a dangerous misconception that floodplains are completely safe, encouraging inappropriate development in vulnerable areas. This “risk creep” increases potential damage if a flood exceeds the dam’s design capacity.

- Climate Change Uncertainty: Changing weather patterns and more extreme precipitation events challenge the original design capacities of older dams, requiring constant re-evaluation and potential upgrades to remain effective.

Conclusion

As we’ve explored, dam flood control is a sophisticated and indispensable aspect of modern water management. Dams are complex systems, offering remarkable benefits in protecting lives, economies, and infrastructure from devastating floods. They actively manage water, not just store it, through intricate operational strategies that balance diverse needs like water supply and power generation.

Yet, we recognize that these benefits come with significant environmental and social considerations, alongside the critical imperative of dam safety. The challenges posed by climate change further underscore the need for continuous innovation and adaptation in our approach to flood management.

At FDE Hydro, we are committed to being at the forefront of this evolution. Our innovative modular precast concrete technology is designed to deliver faster, more cost-effective, and sustainable solutions for new and retrofitted dams. We believe this next-generation approach is vital for enhancing flood control capabilities and strengthening hydropower infrastructure across North America, Brazil, and and Europe, paving the way for more resilient communities and sustainable water resources.

We are proud to contribute to the future of Sustainable Water Infrastructure. To learn more about our vision and solutions, please visit our page on Learn more about the future of Hydropower.